‘

A (sketch) book is a great metaphor for a life … it has a front and a back cover and it’s bigger on the inside than the outside. —Chris Ware, artist

Opening an artist’s sketchbook is like stepping over a threshold into a private and discrete interior world. What you may find there is intimate, immediate, undigested, and unlikely to have been created for sharing. Yet what is most powerful in the drawings, paintings, collaged items and notes in any artists’ sketchbooks is the insights they may grant into an otherwise invisible daily practice and the artist’s preoccupations, ideas, musings, and experiments. It is a vista into a life within a particular place and time.

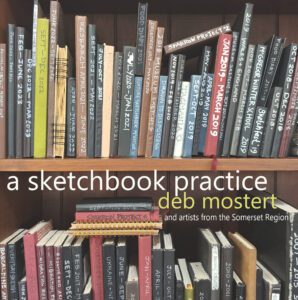

This is the second exhibition of Deb Mostert’s sketchbooks, with the first held at Ipswich Art Gallery, the closest regional gallery to her home, in 2023. The ongoing interest in these volumes of drawings and notes tracing 30 years of an art practice relate to the variety that they offer even a casual observer. It might also be generated by Mostert’s wide teaching practice through which school students, adults and other artists access her enthusiasm for documenting daily experience. For most however, I suspect that their interest is stimulated by the aesthetic pleasure to be had in these volumes.

On any spread of pages, the freshness of Mostert’s sketches, her ability to conjure the essence of a magpie, a wallaby, or a dog, and harness the feeling of being in a landscape or place, or to really see the person she intuited through deft strokes toward a portrait, together with her handwritten notes, offer up insights that creep under your skin and into the memory.

Her media is simple and easily carried in her pocket—generally a simple pen, infilled and extended with watercolour paint and gouache, with sketches brought to life, rising from the raw pages of each book. For Mostert this habit is ‘a ritualistic thing that you do. Drawing helps you to see, and to observe and learn from nature, real life.’

Perhaps most powerfully in these volumes is the opportunity to look for connections between this artist’s life and their work. It’s an old art historical chestnut, the concern about what comes first—the art or the life. Not all contemporary critics believe that the artist’s life (outside the work produced for public scrutiny) offers useful material in terms of understanding the art. Personal narrative may be resisted, despite speculation since Giorgio Vasari’s Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors and Architects (1550-1568). And, more recently, art historian Colin Eisler, who writes that ‘if an artist’s work is worthy of scrutiny, the more we know about the artist the better’

Certainly, Mostert’s sketchbooks are produced in private for herself; she admits to feeling ‘exposed’ through their exhibition, with a level of anxiety that is acknowledged alongside her choice to share them. She said, ‘They are paradoxically separate and the same parallel stream to my art practice. They are a place where I can be at once comfortable and anxious, more so than when making work for public exhibitions. They are my place to be a human living thing. This is how I deal with life.’

As an artist, Mostert produces public art and gallery exhibitions, which explore the meanings attached to objects and collections, natural history, changes to the environment, and also her own Dutch family’s migratory history, with many parallels connecting these themes. Each of these subjects are touched, deeply and lightly, in these pages. She may document visits to museums and into nature, a fascination with taxidermy and its necessities. Then there is her home in a gully of forest, the impact of changes of weather, and her daily interactions with lizards, birds and other wildlife. Not exposed in her public practice but visible in her sketchbooks are her immediate family and friends, her faith, and a broad connection to her community.

A humanitarian concern with social justice emerges with drawings of refugees at meetings, portraits of individuals. Spiritual touchstones are fleshed out with words and scripture, exploring concepts like hope, accompanied by an image of a colourful seahorse which quivers, its life force captured on a page. And Mostert’s sense of her own significant legacy as a human being and an artist emerges with drawings of busts in museums and sketches of Master copies noting the artists, rulers, philosophers and apostles who have gone before.

Her sketchbook practices were shared in workshops with local Somerset artists earlier this year. Using concertina books that may document a day in the life, with themes of landscape, still life and people, local artists have contributed their visual musings to Mostert’s in this exhibition, illuminating a palpable sense of what this region contains, recorded by its people.

There is unstinting honesty and authenticity in Mostert’s sketchbook practice, with her selections committed to sharing the gamut of her process and person. She wrote in a manifesto for the Ipswich exhibition that her sketchbooks help her to see, ‘fostering gratitude, concentration, observation and contemplation’. In the volumes and pages opened to The Condensery audience, we experience the seamless nature of Mostert’s present, the way that art-making opens her psyche, and an artist, like her sketchbooks, ‘bigger on the inside than the outside’.’

8 April 2024 Louise Martin-Chew